It’s been a tumultuous year for global energy markets; the Ukraine conflict exposed Western Europe’s over-reliance on Russian hydrocarbons while COVID lockdowns crimped demand across Asia. We recently travelled across Asia to try and make sense of global gas market volatility and better understand the outlook for energy over the short, medium, and long terms. We spoke to key Japanese, Chinese and broader Asian regional gas buyers, utilities, traders, and industry consultants to discuss the outlook for international gas markets and the approach to decarbonisation. Overall, the discussion was reasonably constructive, albeit with an expectation of ongoing price volatility. More importantly, we returned with increased conviction regarding the long-term outlook for gas to 2030. It was clear that gas will continue to play a key role in facilitating the reduction of higher carbon fuels like coal to help economies meet their energy transition goals.

A review of ’22

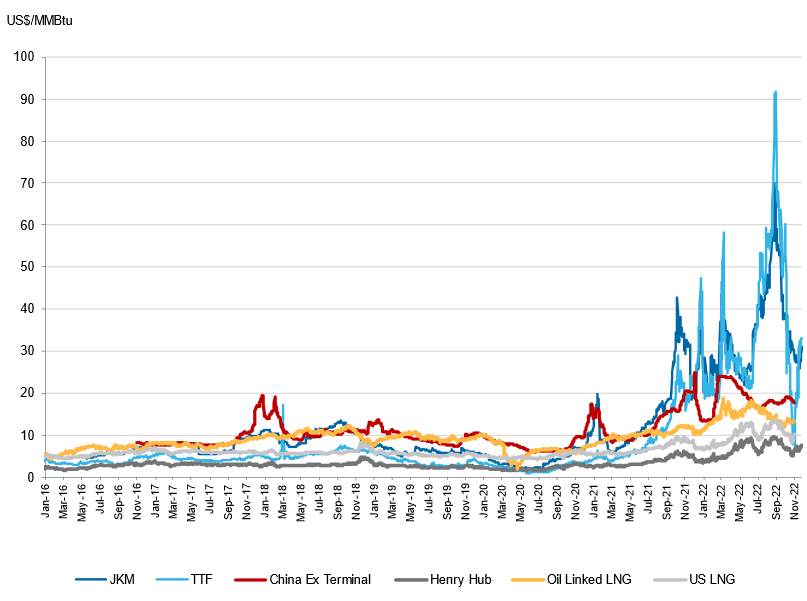

This year has been challenging for global energy markets, with the combined impact of COVID lockdowns and the Russian/Ukraine conflict creating unprecedented volatility in international oil and gas prices. However, the setup for 2022 started well over a year ago as we approached the northern hemisphere winter of 2021 when European and Asian gas prices broke out of their decade-long malaise (see Figure 1). This was driven by a multitude of factors: (i) elevated demand out of Asia, particularly China; (ii) high oil prices driving more buyers into the spot market rather than establishing new oil-linked term contracts; (iii) low inventories leading into the Northern winter; and, (iv) potentially an intentional withholding of Russian gas to the West as a prelude to its invasion of Ukraine in early 2022.

Roll on to 2022 and the issues in global gas markets intensified. China’s strict COVID-zero policies led to a year-on-year reduction of 69Mcm/d (or around 5% of global LNG demand in 2021) compared to the previous year, but this was dwarfed by Europe’s massive ~150Mcm/d increase in LNG demand as Russian gas reduced to a trickle leading to record high gas (and electricity) prices in Europe.

Figure 1: Global gas prices have had a tumultuous couple of years

Source: Macquarie

Changing buyer behaviour and concentration to US exporters creates risk

Our engagements with regional Asian gas buyers confirmed the unprecedented events of the past two years have driven a significant change in purchasing behaviour, with high spot prices spurring a frantic rush to sign long-term contracts. These contracts have been mostly with US producers, with over 80% of deals announced so far in 2022 being with Gulf Coast exporters (before the recent 27-year deal signed between China and Qatar).

Buyers seem to perceive US producers as being the lowest cost and whilst this may be true on a historical basis, we wonder if this will still hold true beyond 2030. Before the Ukraine conflict, US Henry Hub averaged around US$3/mmbtu which equates to an export LNG price of around US$6/mmbtu FOB, which is cheap versus our long-term oil-linked assumption of around US$11/mmbtu (US$80/bbl Brent on a 14% slope).

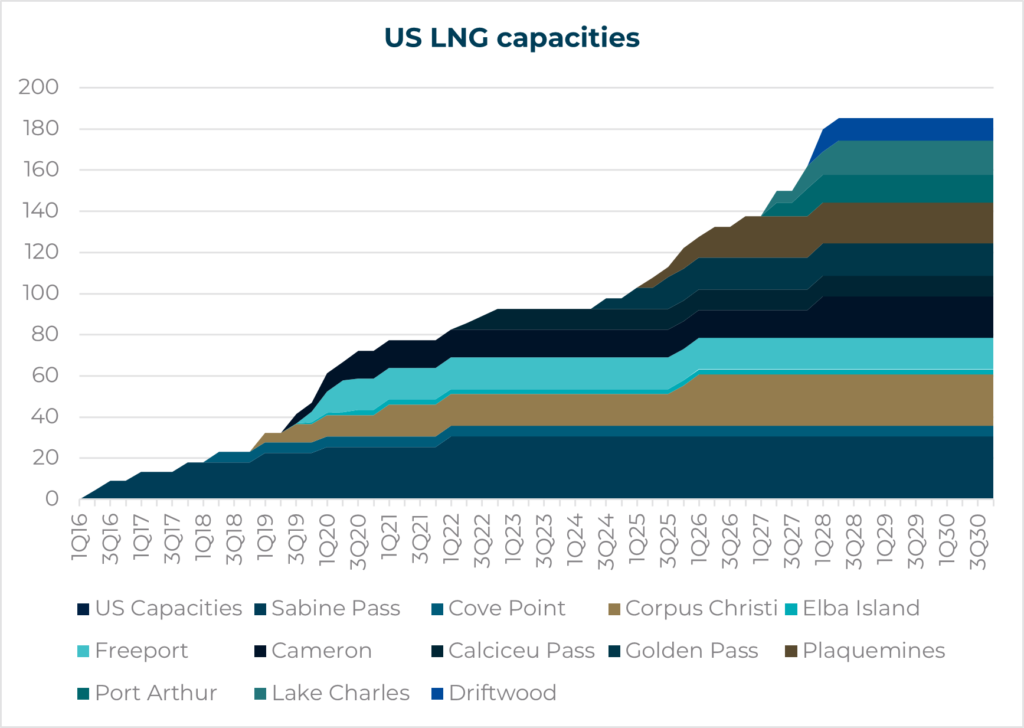

However, with US export commitments of 180mtpa increasing to potentially 200 to 250mtpa by 2030, versus ~80mtpa in 2020, a significant increase in US drilling will be required to meet this demand. Henry Hub will need to rise to around US$7-8/mmbtu to reach parity with our long-term oil-linked assumption. This is broadly in line with where spot levels are now. Indeed, Henry Hub-linked contracts exceeded oil-linked prices for the first time in September this year.

Based on our conversations, we believe buyers have swung too far to the US, with ~73% of all term supply beyond 2035 set to come from the US. US gas exports currently account for around 10% of domestic production, but this could rise to over 25% by 2030. It is uncertain what this additional demand draw will do to US gas prices, but it does present a significant geographical risk to energy security by the end of the decade. Given the lessons learned from the impact of Western Europe’s over-reliance on Russian gas, we expect buyers will again look to Asia-Pacific conventional supply to diversify their source risk. The recent 27-year deal between Qatar and China’s Sinopec is likely the beginning of this shift, followed by Santos’ Papua LNG project for either Chinese or Japanese offtake support, and new Woodside offtake agreements as its Pluto contracts come up for renewal.

Figure 2: US LNG capacity forecasts

Source: Macquarie

Japan’s energy dilemma: will they achieve security alongside decarbonisation?

To the credit of the Japanese government, the country has set ambitious decarbonisation targets and, following discussion, with Japanese utilities companies, have put these targets within corporate goals. The decarbonisation plans outline a dramatic shift in the country’s energy mix by 2030: renewables more than double from from 18% to 37%, nuclear restarts lift its contribution from 6% to 21% while coal falls from 32% to 19%, oil from 7% to 2% and gas from 37% to 20%. These targets support a goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. While ambitious targets are needed to spur action, the changing energy mix presents significant challenges which are yet to be overcome.

Japan’s geography does not lend itself to vast swathes of solar or onshore wind, and China’s control over renewable supply chains may mean the pace of the roll-out could be dictated by forces outside of Japanese control. While the Federal Government is keen to see more nuclear reactor restarts from this zero-carbon source, this appears to be largely a local government choice and its influence over prefecture-level decision-making seems limited. That said, public support may increase for restarts as more of the population suffer from electricity cost inflation which has yet to be passed on to most Japanese consumers.

Managing energy security as well as energy transition

If renewables or nuclear fail to meet the Japanese government’s energy mix expectations, there is a risk that Japan may find itself exposed to an uncertain fossil fuel spot market in the future, as many Japanese LNG term contracts end by around 2030. To address this risk, the Japanese Government intends to deliver an updated plan that better balances energy transition with energy security. We expect securing LNG supply into the 2030s will be a key feature, not only via long-term offtake contracts but also via equity investments in upstream projects. We believe the plan will also include critical minerals security and expect rare earths will feature prominently.

Overall, our trip added to our conviction in our overweight position in the energy sector. While a warm start to the European winter may allow the continent to avoid the worst-case scenario of an energy shortage in the short term, Russian gas supplies will be close to zero next year and it’s unlikely that China’s contracted LNG imports will again be redirected to the Atlantic basin. This should create sustained pressure on global gas markets to the benefit of incumbents, with spot market capacity (e.g. Woodside Energy) and those with contracts up for renewal and new projects requiring offtake partners (e.g. Santos). Longer-term valuation support is also evident as we expect new ex-US oil-linked term supply to be signed with slopes of around 14%, well above the ~10% levels signed two years ago.