2021 saw a rapid increase in cybercrime due to COVID-19. What drove this surge? And what are governments and the private sector doing to protect the economy, business, and consumers from the threat of a cyber-attack?

COVID-19 creates cyber pandemic

One of the lasting impacts of COVID-19 has been a greater reliance on retail online activity and widespread business adoption of working from home. Businesses responded by accelerating their operating models online.

The impact of our increasing reliance on technology during the pandemic has created additional opportunities for cybercrime. Cybercrime covers a broad range of malicious activities such as theft of data, money, demands for ransom, and the use of computing storage and processing power.

The cost to business of cybercrime includes business preparedness, loss of trade through interruption, investigation, recovery, and damage to brand and reputation.

The threat to banking, insurance, and other financial services industries due to the emergence of cyber risk over the last 20 years led to financial regulators imposing stringent obligations on them.

Corporate law to protect personal data has also been legislated, enforcing companies to disclose any data loss, and establishing protection standards. Corporate governance best practice now requires companies to report cyber risks and allocate resources to protect and respond to cyber breaches.

How big is the problem?

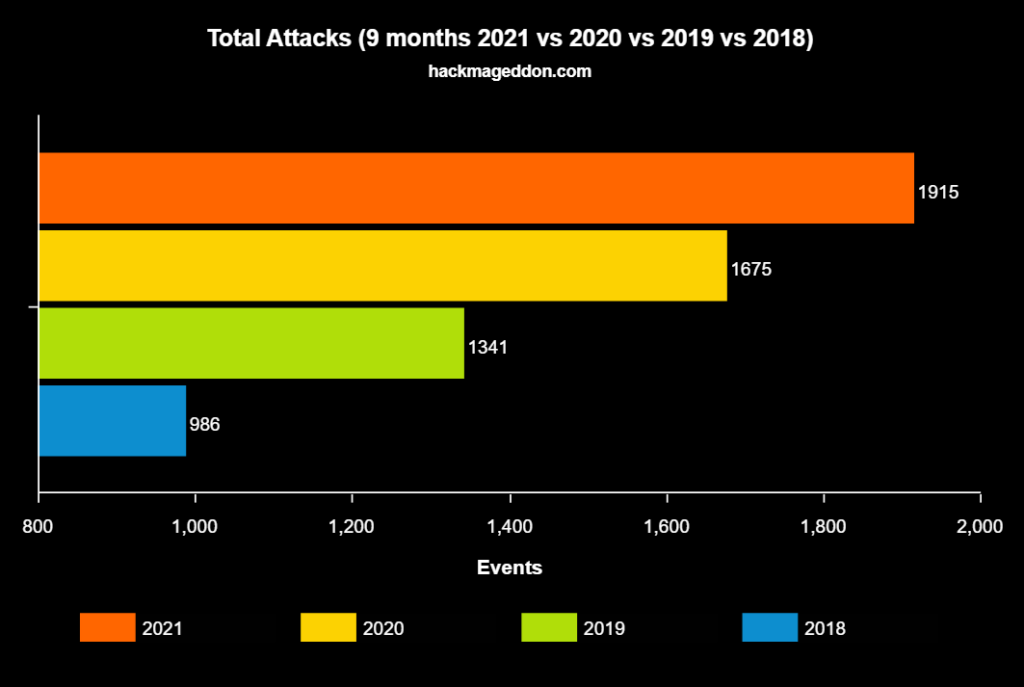

Cybercrime industry veteran Paolo Passeri hosts hackmageddon.com and maintains timelines of publicly disclosed cyberattacks. The website shows an increase of 24% in cyberattacks in 2020.

Chart 1. Increase in global cyberattacks (2018-2021)

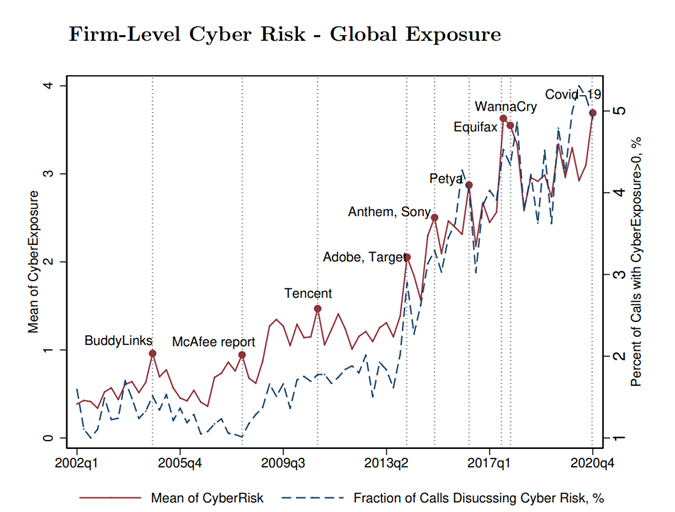

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper: The Anatomy of Cyber Risk by Jamilov, Rey, and Tahoun (JRT) examined the incidence of corporate references to cyber risk and cyber security. Utilising natural language processing to analyse the transcripts from quarterly earnings calls of over 12,000 firms from 85 countries over more than 20 years, the authors counted the incidence of those companies referring to combinations of cyber risk terms.

The chart below shows a six-fold increase in the percentage of companies that have mentioned cyber terms in quarterly earnings calls incidence from 2002 to 2020. The acceleration from 2013 largely reflects the Snowden leaks and the user data breach incidents of Target (~40 million) and Adobe (~150 million). The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that cyberattacks increased 22% in 2020.

Chart 2. Firm-level global exposure to cyber risk

What’s the cost of cybercrime?

Ransomware is one form of cybercrime. It is malicious software designed to block access to computer systems until a ransom is paid. Initially targeting individuals, businesses are now increasingly being targeted and face an added risk of extortion by threats to disclose stolen data. The method used to block access is typically by encryption and the ransom demand is in exchange for a key to unlock systems.

Emisoft, a cyber consulting firm, offers a ransomware identification service called ID Ransomware. Global submissions to ID Ransomware increased to 506,185 in 2020, with a total combined ransom demand of US$18.7 billion. The estimated cost to businesses, allowing for downtime, equated to US$93.5 billion.

Australia made 2,775 submissions to ID Ransomware [through the same period] with a ransom demand total of US$106 million and an estimated cost to businesses of $650 million in 2020.

Emisoft believes that only 25% of Ransomware attacks are submitted. Underreporting is due to stigma, risk of flagging weakness that encourages repeat attacks, and damage to corporate reputation. To allow for systematic underreporting, total potential cost estimates are around four times larger than reported.

Two recent patterns of attack stand out. The first was a series of attacks on infrastructure assets where the motive was to threaten disruption to the community on a large scale. These prominent attacks saw a step-up in the ransom amount, forcing the closure of critical infrastructure including the US East Coast Colonial Energy Pipeline, the disabling of Ireland’s Public Hospital IT systems, and shutting down Sweden supermarket chain Coop.

The second was a series of highly effective targeted IT supply chain attacks where a set of system administration tools were breached and automated software updates by the firms then deployed ransomware to businesses on a magnified scale.

To put this into perspective, the World Economic Forum estimates 18,000 SolarWinds, a US software business that helps manage networks, systems, and information technology for most of the Fortune 500, were impacted by the breach.

Systemic underreporting and delays in disclosure slow the identification of new threats. Payment of ransoms perpetuates cybercrime and the recognition that companies increasingly hold cyber insurance – and will therefore pay – has further incentivised attacks.

Estimates of ransoms paid are also based on incomplete data, not only by underreporting but the proportion of victims that pay. James M Murray, Director of the United States Secret Service, laments that the lack of reporting grants perpetrators cover and forfeits any chance of recovery. He credits the agency with the seizure of US$2 billion over the last five years and prevention of losses of US$10 billion.

Adding further pressure to a ransom situation is the fact that paying a ransom is illegal under Australian law. To do so would expose directors to personal liability. If caught by a ransomware attack, they face a tough choice between the consequence to the company of not paying and their liability if they agree to pay.

In the case of the Colonial Energy Pipeline, CEO Joseph Blount conceded that the company agreed to pay a US$4.4 million ransom in part because they were unsure how long it might otherwise take to bring their systems back up safely. The potential compromise to half the east coast’s transport fuel supply was too great a risk. After early reports that Colonial had declined government assistance, the FBI announced that most of the ransom had been recovered by decrypting the crypto coin payment instructions that identified the recipient’s accounts.

Governments acting on cybercrime

President Biden has recently acknowledged that infrastructure ransomware attacks in the US constitute a major national security threat. Meeting with Russian President Putin, he declared: “our message is clear: countries that harbor cybercriminals have a responsibility to act. If they don’t, we will.” President Biden also announced sanctions against Russia for the SolarWinds hack. Biden asserted in a speech that Russian cyberattacks could trigger kinetic warfare, warning: “if we end up in a war, a real shooting war with a major power, it’s going to be as a consequence of a cyber-breach.”

President Biden acted swiftly to sign an executive order to establish strict new government cybersecurity standards. To this end, software sold to the US Federal Government must meet a higher standard and is expected to lead the private sector by example. All federal agencies are required to use multi-factor authentication and encrypted data as part of setting high standards.

A cyber incident review board, that acts like an airline incident investigation team, has been established to track and monitor attacks.

In Australia, the publication of the Federal Government Ransomware Action Plan proposes new laws cracking down on ransomware and cyber extortion, and provides additional police powers to track and seize proceeds of crime.

On 10 December 2020 the Minister for Home Affairs introduced the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Bill 2020 which expanded the list of protected critical infrastructure sectors to include: data storage or processing, space technology, energy, water and sewerage, transport, communication, financial services, defence, higher education, food and grocery and health care.

In addition, the Bill included proposed mandatory reporting when subject to cyberattacks, with additional powers to allow the Australian Signals Directorate to take control of a company’s computer systems.

Company boards have a role to play

The specialised technical nature and language of technology make preparation and planning for cyber risk challenging for boards. The rising significance of a cyber incident brings readiness for response and recovery under appropriate oversight duties established under the Corporations Act.

Bitsight (a cyber rating consultancy) in partnership with Glass Lewis (a provider of global governance solutions) claims that 90% of US Fortune 100 companies have a cyber committee, with at least one director with relevant cyber skills, an increase of 40% over the past five years.

In Australia, disclosure and reporting obligations for data breaches and cyber incidents are established under the Privacy Act, The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) Prudential Standard CPS 234, and the Critical Infrastructure Amendment Bill covering most listed entities in the S&P/ASX 200.

The probable significant consequences of a cyber incident would also incur obligations under the Corporations Act and ASX listing rule of continuous disclosure of market-sensitive information.

Investor Implications

The good news is that business leaders have recognised the risks, understand the consequences of an incident on shareholders and customers, and are aware of existing disclosure obligations in the event of a cyber-attack.

A 2021 survey of 121 businesses conducted by Insurance broker AON, reflected the surge in cyberattacks by rating cyber risk/data breach as one of the highest risks, moving from 5th to 2nd place.

On 6 August 2020, the Australian Government released the Australian Cyber Security Strategy 2020, which plans to invest $1.67 billion over ten years. This latest version has built on the 2016 Cyber Security Strategy and a 2019 invitation for submissions that garnered responses from industry group representative bodies. The responses highlighted the existing regulatory strength and maturity within key market sectors such as banking, insurance, financial services, and telecommunications.

Mitigation of this growing risk comes at a cost. A value transfer occurs directly through countermeasures and via transfer costs where cyber insurance is available.

Significant capital is being invested in developing new solutions and services to prevent and mitigate the threat of cybercrime. Tyndall AM portfolio holdings that stand to benefit from these investment opportunities include Downer Group and Telstra.

Downer has a well-established division providing engineering and project consulting to Commonwealth defence and cites that it’s contributing to a $400 million cybersecurity capability improvement initiative.

Separately, Telstra has been independently classified as a leader in both cyber security technical services and managed security services by Information Services Group (ISG) in their August 2020 ISG Provider Lens Quadrant report. Revenue for the year to June 2021 for its combined Managed Services, Professional Services, and Cloud applications division grew a combined 8% and now exceeds $1.3 billion.

More broadly, as part of our ESG due diligence, Tyndall AM research analysts assess companies for their potential exposure to, and consequences of, cyber security incidents. This effort informs discussions with boards and management teams of investee companies about their cyber security preparation and touches on other critical aspects, such as a board’s skills mix.