On the wrong side of the ESG equation?

The Tasmanian salmon industry has over recent years come under intense community scrutiny over its environmental conduct with allegations of environmental destruction of once pristine waterways. Media outlets such as the ABC have reported on the effects of salmon aquaculture on the local marine environment, including the creation of dead zones where marine flora and fauna are eliminated.

The result has been reputational damage of local farmed salmon products and increased community opposition to further lease expansions. This has also coincided with a global spotlight on the conduct of offshore salmon farmers and has led to the wider perception that the industry now sits on the wrong side of the ESG equation.

While there is no doubt that aquaculture can have the negative environmental impacts, it is also important to note its relative environmental footprint against competing animal proteins. This recognizes that there is a growing global demand for animal proteins and that the current protein production mix cannot be scaled in an environmentally feasible way.

Bigger footprints a rising challenge

Salmon consumption has grown sizably in Australia averaging ~5-6% per capita growth over the past two decades. This was largely buoyed by thematic tailwinds such as perceived health benefits and general palate changes. Given that Australian production is mainly geared towards the domestic consumption of salmon, the accompanying growth has led to increased farming footprints and the environmental issues that come with it.

Salmon pens produce waste which is a combination of fecal matter and excess feed. This waste increases the concentration of nitrogen and carbon in the water and seabed. This degrades the surrounding environment with detrimental effects on marine fauna. Essentially, the contamination creates ‘dead zones’. This has been observed in other salmon producing nations including Scotland and Norway as well as locally in western Tasmania’s Macquarie Harbor.

The awareness of these issues has resulted in both media scrutiny and increased regulatory intervention. As well as a diminished social license hindering community acceptance of the industry, such scrutiny increases the risk of brand damage. Further, the environmental protection agencies have stepped in and reduced the total permissible biomass in Macquarie Harbor from 16,000 tonnes pa to 9,500 tonnes pa. This reduces the potential revenue opportunities and increases unit production costs.

Not flopping around

Tassal, a Tasmanian-based Australian salmon farming company, has been actively managing these environmental issues including:

- Introducing automated, acoustic-based feeding systems which regulate feed output and reduce the amount of excess feed.

- Locating new pens on open waters with better flow—reducing waste concentration around the pen sites and avoiding benthic deterioration.

- Successful breeding initiatives in partnership with CSIRO producing fish that are more tolerant of warmer water temperatures. This reduces the amount of feed required, as well as increasing the potential number of suitable sites to reduce waste concentration.

In addition to tackling the issues around managing the sustainability of the fish feed:

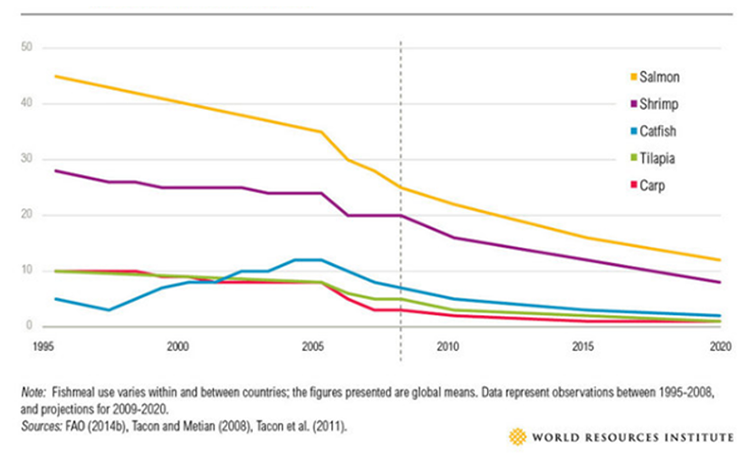

- The industry has seen a sustained reduction of fishmeal and fish oil’s share of salmon feed which is largely sourced from stretched Peruvian fisheries. Whilst the dependency of fish oil and fish meal has reduced materially there is recognition that the forage fish populations will continue to be challenged as a result of increased demand as well as climate change. Tassal and the industry have been exploring emerging alternatives such as microalgae and omega-3 rich canola oil.

Table 1 – The acquaculture industry has reduced the share of fishmeal in farmed fish diets

- Soy protein is also a consistent component of fish feed and it is increasingly important to the industry to ensure that the sourcing of non-fish-based feed ingredients are from sustainable and lower carbon sources. Tassal for example sources their soy feed from local producers and not from operators engaged in deforestation of vulnerable geographies such as the Amazon rainforest.

Balancing the scales

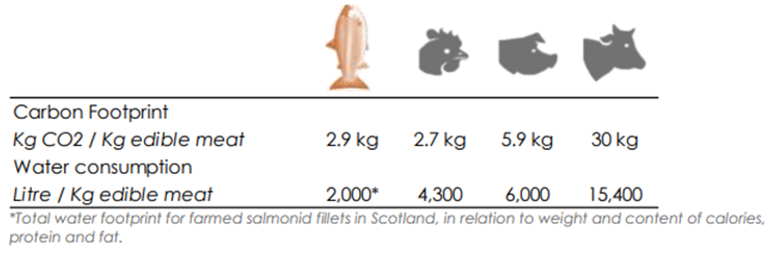

While the industry clearly has some environmental challenges to deal with, it is also important to recognize its relative environmental impact compared to the production of other animal proteins. In short, aquaculture has significant lower CO2 emissions, significantly lower water consumption and minimal land use.

The ‘farmgate’ lifecycle current greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per kilogram of edible meat of salmon is estimated to be ~2.9kg which is less taxing compared to nearly all land-based animal proteins except poultry. Farmed salmon also had one of the lowest feed conversion ratio (FCR) at 1.15x (kg of feed to produce kg of bodyweight).

Figure 1. Climate friendly production

Source: Mowi, Mekonnen, M.M. & Hoekstra A.Y. (2010), Ytrestøyl et. al. (2014), SINTEF Report (2009) Carbon Footprint and energy use of Norwegian seafood products, IME (2013). SARF. (2014) Scottish Aquaculture’s Utilisation of Environmental Resources

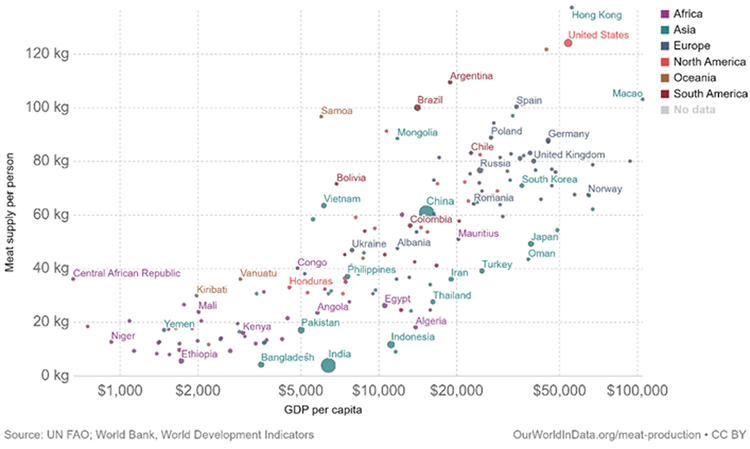

This is particularly important given the expectation of ongoing strong growth in demand for animal protein. According to the UN the global population is projected to trend towards 9.7 billion by 2050, an additional 3 billion people of additional protein demand. Also, as the current developing economies becomes more affluent, it is likely that consumption of meat will increase given observed correlation between meat consumption and income levels, as shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2. Meat consumption vs. GDP per capital

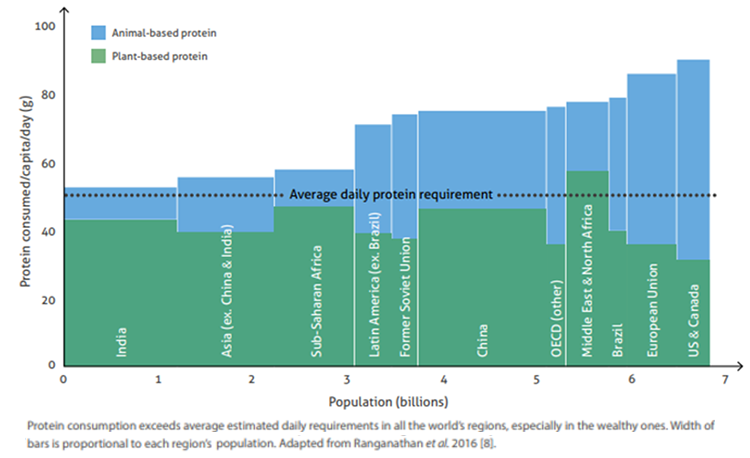

Chart 3 shows the bulk of the world’s population has a materially lower animal consumption profile than most western countries. We expect this gap will continue to converge as the income of developing nations rises.

Chart 3. Average global daily protein requirement

Animal agriculture is estimated to contribute to 14.5% of GHG emissions. The adoption of an animal protein-rich “western” diet by this growing class of consumers would see emissions increase and jeopardize current initiatives to reduce carbon emissions.

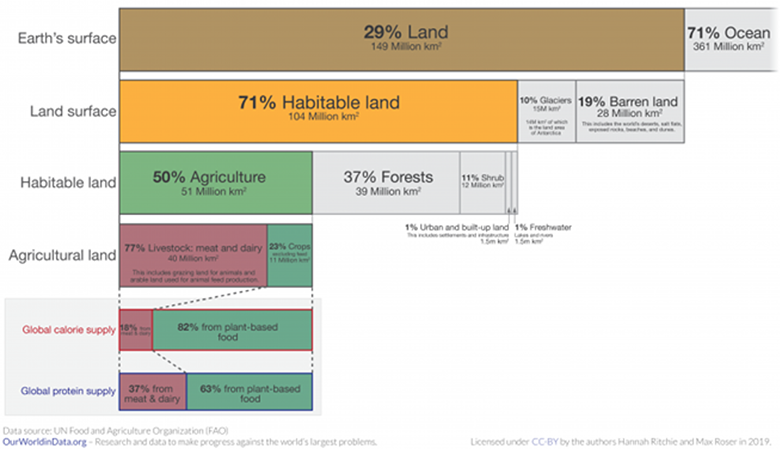

Land based protein also commandeers another valuable resource – land. It is estimated by the Food and Agriculture Organisation that ~38% of all habitable land is utilized to feed and accommodate land-based protein. A greater shift towards plant-based protein or aquaculture would alleviate stress on habitable land and the general encroachment onto forest biomes to sustain current agricultural requirements.

Chart 4. Global land use for food production

Net net – positive

In conclusion, while salmon farming is not without its own unique environmental challenges, the industry is proactively managing these issues and minimizing the impacts. Furthermore, there are environmental considerations to be made regarding the relatively low environmental impacts of salmon farming compared to other animal proteins. In our view, as a comparatively environmentally friendly protein, the industry is well placed to continue to grow salmon’s share of the protein market.